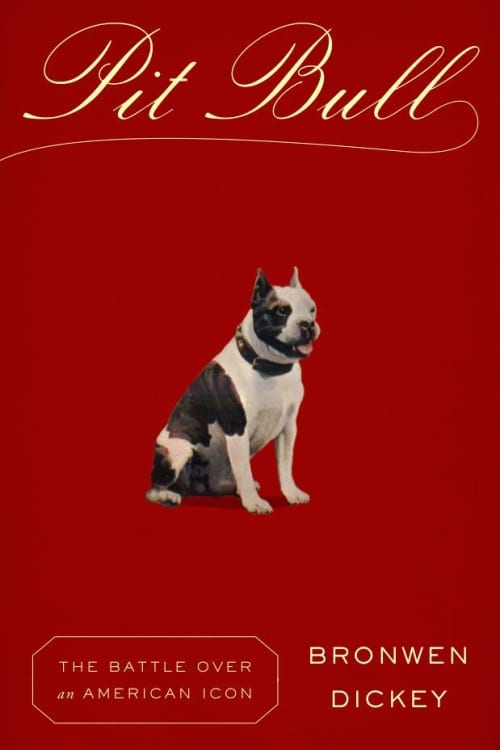

Bronwen Dickey has written a remarkable book about Pit Bulls and the people who love them — and the people who really, really don’t — that you should read as soon as you can.

As soon as you can is May 10 – that’s the launch date for Pit Bull: The Battle over an American Icon.

Pit Bull is gorgeously written and answers questions you may have had forever about these dogs — like what, if anything, makes them different? And why do these dogs have difficult reputations?

It also gets into parts of the history, community, and policy issues you may not have even realized you needed to know, but will be so glad to learn about.

Dickey also provides advocacy tools that’ll be helpful to folks who are trying to do right by these dogs — and who are especially trying to do right by communities of people and dogs together.

Really, this book is outstanding. If you love dogs, you should read it. (If you don’t love dogs, we’re not sure why you’re visiting BarkPost — but thanks for coming! We’ll go ahead and recommend you secure a copy, too.)

We caught up with Dickey by email in advance of Pit Bull‘s release — May 10, in case you forgot — to pick her brain a bit more about our blocky-headed friends and their complicated place in society.

This should be a simple question, and yet it’s not: What is a Pit Bull?

As I say in the book, if you ask a hundred different people, you will get a hundred different answers.

Devoted fans of the purebred American Pit Bull Terrier prefer the term “Pit Bull” only be applied to their dogs, and for a short time in the 19th century it was, but unfortunately for them the label grew and changed a lot throughout the 20th century.

As time passes, the category simply keeps getting bigger, at least in terms of how casual observers use it. As of right now, that label contains not only four pedigree breeds (the American Pit Bull Terrier, the American Staffordshire Terrier, the Staffordshire Bull Terrier, and the American Bully), but also mixed breed dogs with blocky heads and short coats.

These dogs may have one of those four breeds in their genetic heritage, but they also may not. In addition to that, numerous other pedigree breeds (such as the Boxer) are closely related to the Pit Bull breeds and often visually similar.

The science of canine genetics is such a complicated discipline.

Did you come out of reporting and writing this book thinking differently about Pit Bulls, or anything else?

Almost every assumption I had was dislodged, or at least challenged at some point. Every single aspect of the story of Pit Bulls in America (the history, the science, the culture) had more layers than I ever imagined, especially when I dug into common beliefs about who the average Pit Bull owner is and what motivates him or her.

There was a lot of race and class animosity hiding in those stereotypes that revealed a much larger divide than I thought was there. I started the book believing that I was writing about dogs, when really I was writing about people.

You’ve said you went into this research wanting to answer some questions: How did we get here? How did one type of domestic dog become such a lightning rod for fear and hate?

Do you have an answer?

The well-intentioned (and necessary) effort to felonize dogfighting in the 1970s spun into an out-of-control media free-for-all during a time of significant social upheaval.

The hype about the dogs then made them popular with a lot of people who were already seeking out dangerous animals, and had been doing so for years.

One thing built on another until the whole thing became a giant self-fulfilling prophecy, and all the normal families living normal lives with their normal Pit Bulls got caught in the storm.

It seems like everyone loves this book, for good reason — except the anti-Pit Bull community. Can you tell me what it’s been like being on their radar in this high-profile way?

Thank you for saying that everyone loves it, but oof, that’s definitely not true!

The anti-Pit Bull contingent spends a lot more time thinking about me than I spend thinking about them, that’s for sure. One of the things I did come to appreciate while researching the book, however, was how much emotional pain many of these people are in.

[bp_related_article]

While I think breed-based laws are terrible policy and that we need to stop focusing on breed as the only significant factor in dog behavior, I also think that reckless owners who allow their dogs to injure others need to be held much more accountable.

I can’t imagine the anger, fear, and frustration I would feel if a reckless person allowed their dog to harm me or my pets, and then skated off into the sunset, while I was left with psychological trauma and a big stack of medical or veterinary bills. That simply shouldn’t happen. As a society, we can do better than that, and we need to.

In terms of specific harassment stuff, it turns out that the old adage “all publicity is good publicity” is true. A significant number of strangers and media outlets have reached out to me saying, “I’m not even interested in dogs, but I bought several copies of your book because I saw someone say something cruel about you online and I dislike that kind of behavior,” or “We want to cover this book because it’s being targeted by protesters,” etc.

If someone wants to have a civil discussion about the facts, then I welcome disagreement and debate completely, as any writer should. We all have something to learn from each other, and we should be willing to listen and engage with different ideas. But there’s nothing productive about personal attacks. People who employ them easily discredit themselves.

I suppose this is a spoiler, but you end the book basically adopting the view that it’d be better to focus on dogs more broadly, or even better than that, on communities of people and dogs, and less on Pit Bulls as a specific category.

What are the best ways to do that? How can we make the world better for all of us so that more dogs, including Pits, are safely and happily in loving homes?

I truly believe that the very best thing we can do to improve the lives of American animals is to fight for safe, humane, equitable, compassionate communities for all American people.

In neighborhoods where residents feels safe at night, for example, you don’t have a thriving market for unstable guard dogs. One study of cruelty complaints in Philadelphia found that instances of dogfighting were correlated with the number of abandoned and condemned buildings. That tells us that these are social problems that have many layers.

While cruelty and neglect can certainly happen anywhere, you don’t see nearly as much of both in places where people have easy access to factual pet care information and veterinary services.

Yet there are thousands of Americans who live in zip codes without so much as a convenience store that sells pet food or leashes, let alone a vet clinic. They love their animals just as much as someone who lives on Park Avenue does, they just don’t have access to the same resources.

If I could boil everything I learned down to one idea, it would be that animal welfare and human welfare are inextricably intertwined, and you can’t help animals without being invested in what happens to their people.

What does your own dog think of your book?

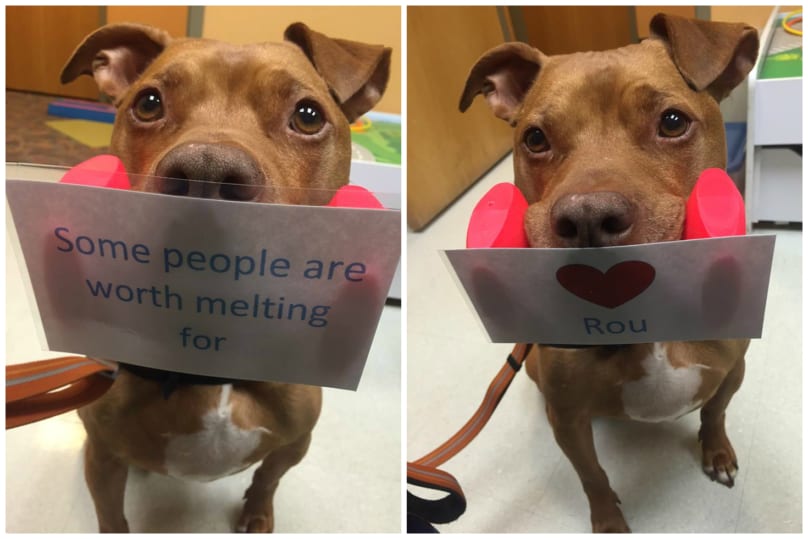

I have a shelter dog who may or may not be a Pit Bull (wink, wink), and I am pretty sure that she is terrifically bored by all this work I’m doing.

If it doesn’t involve walks or peanut butter or spooning, she isn’t interested. Fortunately for both of us, I’ve learned how to spoon her and type at the same time. I’m doing it right now!