An alarm on my phone reminds me three times a day to pause and take a conscious breath. I call it my “Awakening Alarm,” and sometimes I shut it off without pausing and go right back to browsing my Instagram feed, or mindlessly eating some pizza, or obsessively worrying about work. In this busy, insta-gratification and appearance-obsessed society, it’s hard enough to slow down and deepen your awareness of the present moment. But it is even more challenging when the present moment involves a level of pain and suffering you desperately don’t want to feel.

In high school, when my father started drinking himself to death and our family fell apart, I longed for relief from the grief and anxiety that anyone who has ever loved an addict knows all too well. I craved a lucid, single-minded state – to turn my heart and mind off.

I discovered bulimia.

Usually around midnight, I became ravenous in a way that was beyond the physical. I’d sneak down into the kitchen and take a bite of a granola bar, and then another bite, and then another. Soon my teeth were crunching down hard on candy and chips and cookies, all the food I wouldn’t dream of touching during the day. With the sensation of food sliding down my throat, my mouth constantly moving, my belly growing fuller and tighter by the second, I’d soon forget about my drunk dad and bad math grade and the boy I liked who didn’t like me back. I’d soon forget I had a care in the world. My hands were usually covered in peanut butter or the cold pasta salad I dug my fingers into. There was no time for forks or plates or drinks between bites. There was only the desire to fill up, followed immediately by an urgent need to get empty.

When I threw up for the first time, I didn’t know that it would eventually devastate every area of my life, from my relationships to my dreams to my teeth. I didn’t know that in five years I would be hospitalized and living in a rehab center with women who were too thin to walk from only eating things like computer paper and miniature carrots. I didn’t know that I would wake up with raw knuckles, bloodshot eyes, and the feeling that my throat was on fire, and that would be normal. I didn’t know that for eight years, I’d grow sicker and sicker until I was vomiting up to twenty times a night.

What appeared on the outside to be a destructive weight loss method was actually a persistent attempt to escape my internal reality, the thoughts and emotions that seemed too big to handle. Recovery would be less a matter of healing my relationship with food, and more about healing my relationship with the present moment.

[bp_related_article]

Turns out my father and I were not so different. Dad drowned his pain in seas of vodka and denial, while I stuck my fingers down my throat and reached all the way to my heart, trying to yank it out. Both of us were trying to escape our suffering, and hide our vulnerability. We died in small fits over and over again, trying not to feel.

Shortly after rehab, I got a job working with homeless animals at the San Diego Humane Society. It was there, in little doses, that I began making room in my heart, instead of my stomach, for the uncomfortable. Whenever I felt anxious or depressed or overwhelmed, I’d find a big dog, usually a Pit Bull who believed she was a lap dog, and I’d hold onto her bulky body like an anchor as waves of emotion passed through me. When every molecule of my being wanted to numb out and run away, she’d help me to feel and stay. With a nonjudgmental presence, a creature that knew no other way of being than in the here and now, I could drop my methods of self-protection and let my tender, real, vulnerable self be seen.

In The Gifts of Imperfection, Brené Brown describes how in its earliest form, the word “courage” was not associated with heroism or outer strength, but with inner-truth and vulnerability. It is derived from the latin word, “cor,” and originally meant, “To speak one’s mind by telling all one’s heart.”

In my opinion, this is what shelter dogs do. With the language of their bodies, they tell all their hearts. If a dog wants to be left alone, she keeps her distance. If she is afraid, she trembles and tucks her tail. If she wants love, she pushes her nose through the bars and reaches for it. She leaps into your lap. She greets you with an enthusiasm that seems like it doesn’t belong in such a dark, barren place.

A few years ago, while volunteering at a rundown Los Angeles animal shelter, I met a ten-month-old brindle Pit Bull named Sunny. She was abused and neglected as a puppy. In the last kennel in the back corner of the shelter, she was so skinny that even her shadow looked bony. Her tail was cut and broken in several places, as if someone had taken a hammer to it.

Every time I approached her, she whimpered with joy and pushed her muzzle through the rusted bars. Her eyes were so intensely expressive, filled with gold and brown hues. She often looked on the verge of speech, of saying something sad but true. I’d kneel down before her and reach in through the bars to scratch her flanks, to kiss her wet nose, to tell her that she would be okay. She’d lean her body into mine with eagerness, twisting her head to look up into my eyes, squinting in the sunlight.

Sunny knew that she didn’t belong in a cage, separated from the sights, sounds, and smells of the world that made her feel alive. She didn’t own her captivity or make herself comfortable. She didn’t pretend that things weren’t so bad or accept how small her life had become. She remained at the front of her pen, pushing her nose through the bars, telling the heartfelt truth.

In this desolate environment, many shelter dogs behaved as I would if I were trapped in a cage — they deteriorated mentally and physically. But Sunny actually took steps towards healing. She overcame her fear of her reflection in her water bowl and hydrated in the hot summer sun. She began eating again, taking her first bite of kibble from the palm of my hand. And rather than fearing humans or giving up on us all together, Sunny stayed connected.

In the end, the ability to be real and vulnerable saved her life.

I think it’s saving mine, too.

My recovery, from depression and bulimia, has been built on my ability to acknowledge what I’m feeling in the moment (rather than running from it). To let go of my methods of self-protection and ask for help. To drop the “brave” face and put on my real one. To give someone the honest answer when they ask how I’m are doing.

To be more like a shelter dog, and tell all my heart. Even when it hurts.

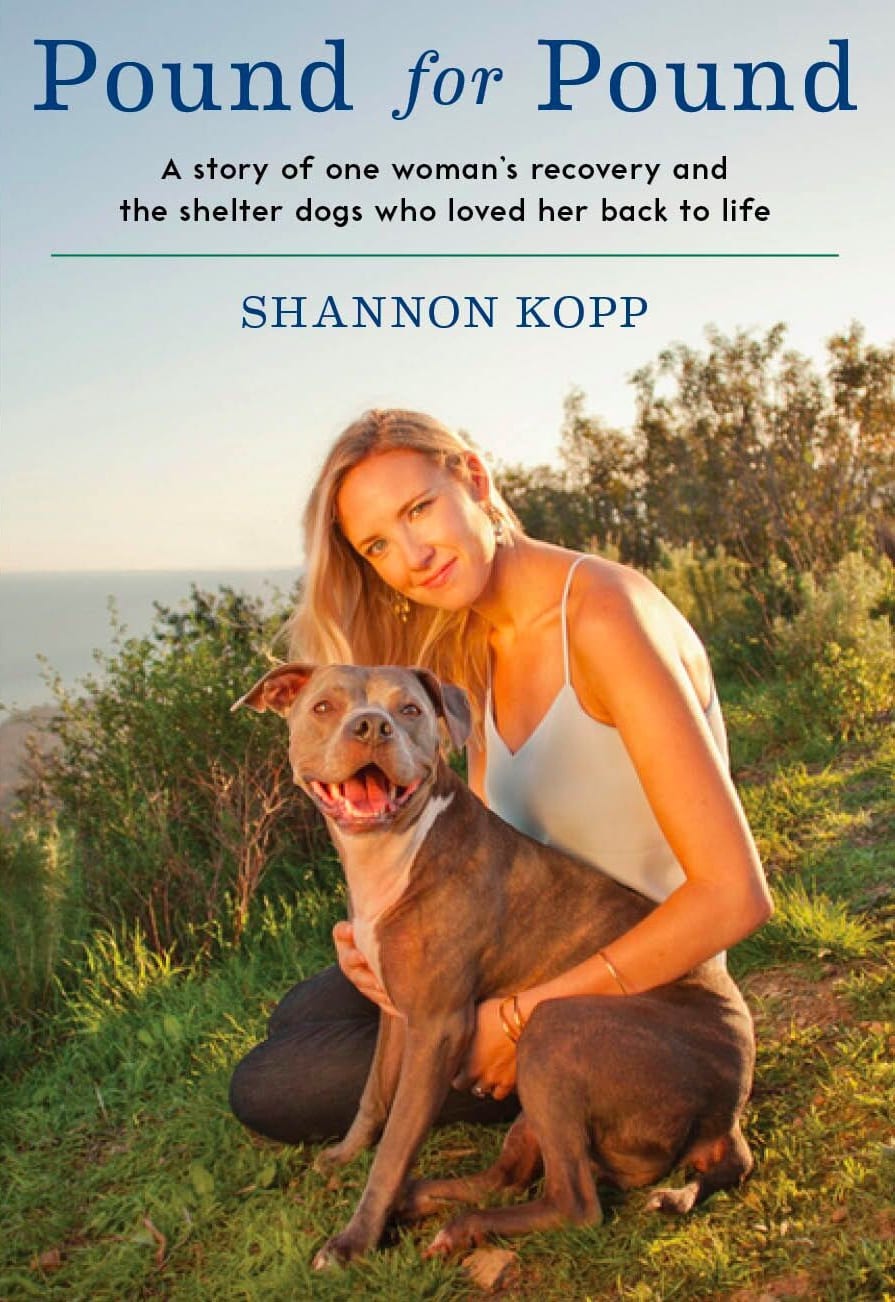

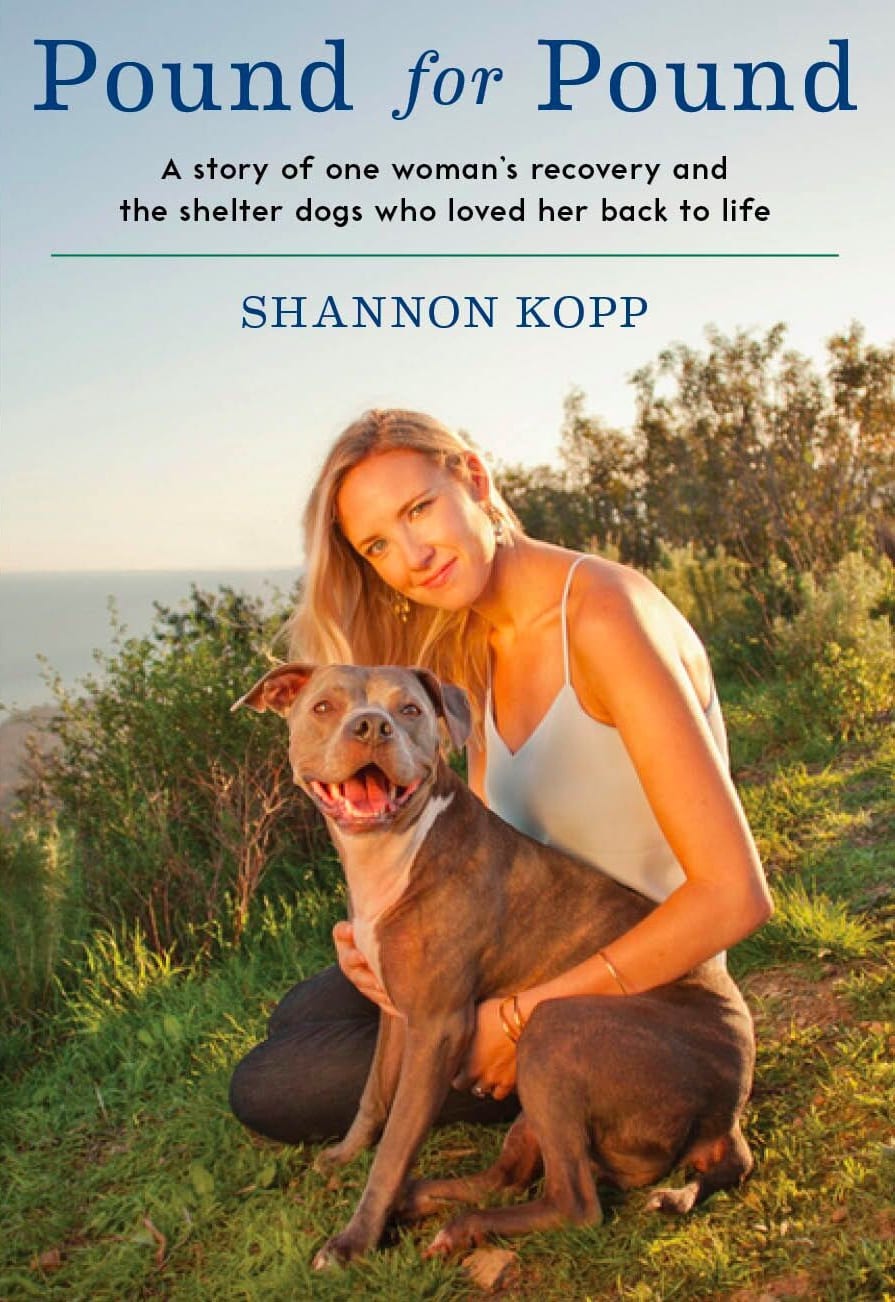

© 2016 Shannon Kopp, author of Pound for Pound

Author Bio

Shannon Kopp, author of Pound for Pound, is a writer, eating disorder survivor, and animal welfare advocate. She has worked and volunteered at various animal shelters throughout San Diego and Los Angeles, where shelter dogs helped her to discover a healthier, more joyful way of living. Her mission is to help every shelter dog find a loving home, and to raise awareness about eating disorders and animal welfare issues.

For more information visit her website www.shannonkopp.com

Featured image via Shannon Kopp