The cruelty of human beings is never surprising, which is a tragedy in and of itself. Every day there are multiple news stories about the terrible things we do to people, to animals, and to the world around us. Oftentimes it’s for petty, selfish, or much more repulsive reasons. It’s the reality of our world, and sometimes it makes it difficult to acknowledge the good things people do, plentiful though they may be.

When it comes to our treatment of dogs, there are few activities as despicable as dogfighting, which The Humane Society of the United States defines as “a sadistic ‘contest’ in which two dogs – specifically bred, conditioned, and trained to fight – are placed in a pit (generally a small arena enclosed by plywood walls) to fight each other for the spectators’ entertainment and gambling.” Sadistic is absolutely right. I would also add “forcibly” to just about every verb in that definition, just for good measure – forcibly bred, forcibly trained, forcibly fought, and so on.

The History of Dogfighting

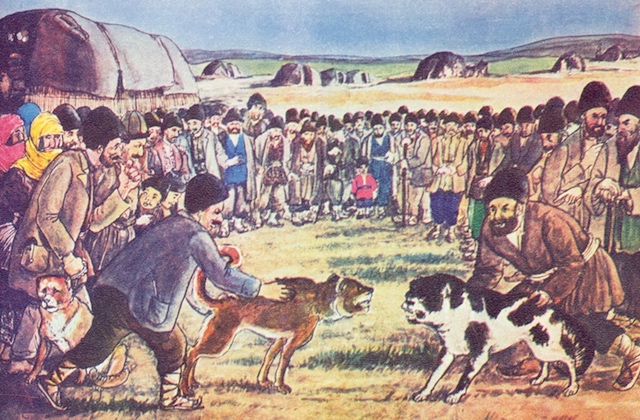

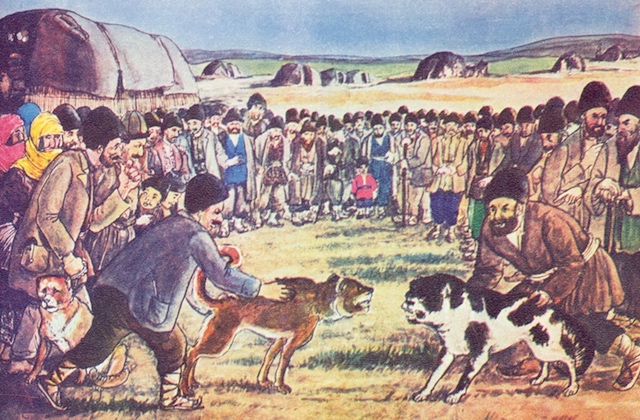

Dogfighting isn’t a new “sport.” In fact, it can be traced all the way back to the Roman Empire, where dogs were pitted not against each other, but against other animals – elephants, bulls, bears, and humans (gladiators) – in the Roman Colosseum. The dog of choice back then was the English Mastiff (or an ancestral variant), followed much later by the Old English Bulldog.

As the centuries went on, bear and bull-baiting became more popular, especially in the British Empire. Queen Elizabeth the First even bred her own Mastiffs for the express purpose of entertaining foreign guests.

Baiting involved tying bears or bulls to an iron stake, at which point dogs would be loosed to scratch and bite at them. Eventually, as bears began to become scarce in the area, bull-baiting became the sport du jour – the bulls would be slaughtered for their meat immediately after a fight – until finally, in 1835, the Cruelty to Animals Act outlawed all blood sports in Britain.

Unfortunately, the passing of this law only led to the popularity of dog on dog fighting as a sport. Illegal though it was, it was much more difficult for authorities to crack down on than bull-baiting as it required far less space. Whereas the Old English Bulldog was the popular fight dog for baiting bulls, watching two Bulldogs go at each other would apparently make for a rather boring fight (they were trained to pin and hold bulls, not move around a lot), hence they were crossed with Terriers – more nimble and dexterous – to create the Bull and Terrier dog. From the Bull and Terrier came the dog that would eventually be known as the Staffordshire Bull Terrier, as well as the American Pit Bull Terrier and the American Staffordshire Terrier.

Dogfighting Today

Though dogfighting bans began to pop up in the U.S. starting in 1867 (embarrassingly, it was not federally banned until 1976), it’s been a prevalent American blood sport in the many years since. According to the ASPCA, experts tend to divide modern dogfight activity into three categories: street fighting, hobbyist fighting, and professional fighting.

“Street” dogfighters usually put on very informal dog fights, sometimes on street corners, sometimes in back alleys, oftentimes without any actual rules. These fights are typically spontaneous and “triggered by insults,” taunts, or turf invasions. The dogs in these fights aren’t particularly well-trained or conditioned, and medical treatment is not a priority, if they receive any treatment at all. It is not uncommon for ACC workers to find these dogs on the street, in dumpsters, et cetera, having been left for dead.

“Hobbyist” dogfighters are a little bit more organized than street fighters. They participate in formal fights a few times each year, sometimes even across state lines. They pay more attention to the breeding, training, and treatment of their animals, but they’re still despicable pieces of human filth.

“Professional” dogfighters are like hobbyists on a much grander scale. They usually have large numbers of dogs on their properties and earn money from “breeding, selling, and fighting dogs at a central location and on the road.” There’s a great deal of money at stake for professionals, and they often have ties to other forms of dangerous criminal activity.

There’s also an emerging category of dogfighters that involves celebrities in sports and entertainment who promote their own fights. Michael Vick is perhaps the most (in)famous example of this, having been sentenced to two years in prison, though he served little more than a year. Vick was actively involved with hanging, torturing, and drowning “underperforming” dogs, among other terrible things.

According to the HSUS, more than 40,000 people in the U.S. participate in organized dogfighting, and hundreds of thousands more participate in street fighting. Dogfighting occurs all over the country, in urban, suburban, and rural areas, and is organized by people of all walks of life (spectators have included lawyers, judges, teachers, and so forth).

Why Do Dogfighters Use Pit Bulls?

If you love Pit Bull-type dogs as much as I do, you’ll no doubt come across some misinformed or spiteful person on the Internet positing that Pit Bulls are used by dogfighters because they’re just naturally more vicious or demonic than their non-Bully counterparts.

This is complete nonsense.

There are, of course, obvious reasons for Pit Bulls being the dogfighter’s dog of choice. They’re strong, fast, tenacious, and athletic, and it’s not unusual for them to be dog-reactive (though there are certainly many who love dogs). But then, all of the above could be said about a number of breeds. So why do dogfighters tend to single out Pit Bulls* for their twisted games?

One of the main reasons is that Pit Bulls have been bred specifically to not redirect their aggression toward their human handlers. This is incredibly important because dogfighters, as a part of the blood sport, will have to stick their hands in the fight, grab their dog, and pull him or her out at some point or another. A dog that bites his or her owner is a dog that will be put down – shot, hanged, or tortured to death.

What’s tragic, and sort of tragically ironic, is that the most desirable traits a dog can have – extreme loyalty and an unrelenting desire to please the owner – are the reasons Pit Bulls make such “good” fighting dogs, and yet it’s that association with dogfighting that’s largely responsible for the bad rap that they get.

(*It’s worth pointing out that, while Pit Bulls are the most common dogfighting breed in the States, they are not the only dogfighting breed utilized today. Others include the Dogo Argentino, the Fila Brasileiro, the Tosa Inu, the Presa Canario, and more.)

What Is A Bait Animal?

When it comes to dogfighting, it would be difficult to pinpoint the absolute cruelest element or aspect, because it’s all cruel, it’s all inexcusable, and it’s all disgusting to a degree that I feel ill-equipped to articulate. That said, if someone were to put a gun to my head and make me choose, I’d probably have to go with the treatment of “bait animals.”

What’s a bait animal? Well, it’s even more awful than it sounds. Bait animals are used by dogfighters to encourage aggression in their fight dogs and test their “fighting instinct.” These bait animals are typically tied to a post with their snouts taped shut so that they can’t fight back (in some cases, their teeth are even broken), while fight dogs are set upon them, sometimes tearing them apart. If a bait animal isn’t dead at the end of one of these sessions, they’re often given to the fight dog to kill.

All kinds of animals have been used in this horrific act. Dogfighters have been known to steal pets from backyards – including puppies, kittens, rabbits, and small dogs – but feral animals, free animals obtained via Craigslist, and even passive/submissive dogs in fight litters have all been used as bait animals, as well.

If you’re a BarkPost fan, you may have heard of famous bait dogs like the late great Oogy, Huey of Saving Huey fame, Khalessi, Marley, and so on. These are dogs who were tortured by human beings, permanently disfigured and worse, and yet they’re still full of love and trust for the humans that saved them.

How To Spot Signs of Dogfighting (And What To Do If You Do)?

The HSUS has put together a checklist of signs that someone – perhaps a neighbor of yours – is fighting dogs. Common signs include: Pit Bulls on heavy chains, treadmills, breaking sticks (used to pry apart a dog’s mouth in order to break up a fight), scarred dogs, fighting pits (usually constructed with plywood and splattered with blood), dogfighting literature, a springpole (used to dangle rope or an animal hide above a dog for tugging purposes), a jenny mill or cat mill, vitamins/drugs/vet supplies (including testosterone, steroids, and cocaine), and washtubs and sponges for bathing dogs pre-fight.

If you suspect or witness dogfighting activity, immediately contact the police or your local animal control officer and report it, providing as many details as possible (time, place, reason for suspicions, et cetera).

Major Dogfighting Busts

The Michael Vick bust (2007): When talking about major dogfighting busts, it’s impossible not to mention the Michael Vick bust. While it was nowhere near as big as the largest cases, it was vital for how it exposed dogfighting to the American public, and for how it showed the world that dogs saved from these situations are NOT damaged goods that just need to be discarded. In the end, over 70 dogs were seized. Vick, as previously stated, was sentenced to two years for his crimes and served little more than a year, and he was forced to pay $1 million to care for his canine victims.

The Missouri 500 (2009): This was the largest crackdown in the history of dogfighting. The ASPCA, the Humane Society of Missouri, and the feds all participated in the dismantling of a multi-state (Missouri, Illinois, Iowa, Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Nebraska, and Mississippi) dogfighting operation, which resulted in 27 arrests and over 400 dogs seized.

#367 (2013): The 367 case – thus named because 367 dogs were seized (plus 80 puppies post-bust) – was the second biggest dogfighting bust in history and took place across Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and Texas. Ten people were arrested, and the ringleader – 50-year-old Donnie Anderson of Alabama – was sentenced to eight years in prison, which is the harshest punishment for dogfighting so far.

It’s this final bust that brings us to bright and shiny portion of this piece, where I get to talk about my favorite dog on the entirety of the Internet: a Pibble named Theodore.

Pibbling With Theodore!

Trish McMillan Loehr is a behavorialist and dog trainer who lives in Weaverville, North Carolina. She worked on several dogfighting busts when she was employed by the ASPCA, and two more as a contractor after she formed her own business, Loehr Animal Behavior. Interestingly, when she worked on the Missouri 500 case (as the leader of one of three behavior evaluation teams), it was initially believed that only 5-10% of the dogs involved could be safely placed in homes, but that number ended up being much higher than 50%.

In 2013, as a contractor, Trish was called to work on the 367 case. It was here that she met Theodore, a dog destined to turn “Pibble” into a verb. According to Trish:

Theodore was one of the dogs seized as an adolescent. He didn’t show any particular behavior problems, so was not on my radar for the first seven months that I worked at his shelter. As the case was wrapping up and play groups were becoming a major focus of our behavior work, these adolescents were re-assessed for dog sociability.

As I was heading down from my last ten-day rotation, my friend Amy Cook said, “You have to meet dog #947, we call him ‘the golden boy’ – he can play with anyone. He needs to belong to a trainer!”

It was Theodore, then named Felix (perhaps for his cat-like cropped ears). He was so wiggly and sociable with humans, as well as having phenomenal play skills. He was a favorite of many of us. Truly amazing for a dog who spent his first eight months on a chain and the next eight in an emergency shelter.

As sad as Theodore’s early life was, he was actually one of the lucky dogs. Because he was an adolescent, he was still too young to fight by the time that he was saved in the bust. And frankly, he’s so ridiculously dog-friendly that he probably would’ve just been killed or turned into a bait dog instead.

In fact, Theodore was so good with other dogs that he became a helper dog for the ASPCA trainers, which meant that he helped shy and grumpy dogs learn to play and socialize. Eventually, he was adopted by Trish and Barry Loehr – his “staff” – and joined a multi-species family that includes Lili the Sato, Duncan the Doberman, Kindi the cat, and Joey the horse.

Now, Theodore’s days are mostly spent pibbling. For the uninitiated:

Pibbling is a verb invented by Theodore’s mom to describe the silly things that fun-loving dogs like Theodore do. These include zoomies, bulldozing into legs, leaping onto beds or furniture and knocking the breath out of you, leaping around with joy at about face height, head butts, giving hugs while nibbling your chin, and annoying dog siblings and kitteh and horse friends by arwoofing and trying to make them play.

His Facebook page, Pibbling with Theodore, is dedicated to all his ridiculous antics, like making art (read: destroying things), eating horse candy (read: eating horse poop), unsuccessfully wooing his feline sister, hugging and kissing anyone who will let him, and the list goes on.

Basically, Theodore is the perfect Pit Bull ambassador, and if that’s the sort of thing that matters to you, then you should absolutely go like and share and promote his page. This time next year, I’m hoping that “pibbling” will be an entry in the Oxford dictionary.

To learn more about the 367 rescue dogs, you should definitely follow the 367 Rescue Family Facebook page, as well specific rescue dog pages like The Mighty Finn, The Wondrous World of Wickham, Ruby’s Big Adventure, Totally Zaz, Blue the Rescue Dog, Evan the Survivor, and Sydney Koehl Art with Love from Homer. These animals are living proof of how amazingly resilient and loving dogs can be, even the ones who’ve experienced a tremendous amount of trauma and terror at the hands of those they should’ve been able to trust the most.

Fighting Dogs Can Be Wonderful Family Dogs

There was a time when fighting dogs were automatically presumed dangerous and disposed of after their value as evidence was exhausted. This is extremely disheartening, since these dogs – even if they exhibit dog aggression – are often very fond of humans.

Even more disheartening, however, is that many of them aren’t all that dog aggressive to begin with. According to Trish Loehr:

“On average, it seems around half of the dogs seized at the fight busts I’ve worked don’t have the level of dog aggression needed to be a fighting dog, and can thrive as family pets.

Fortunately, the general attitude toward former fight dogs has changed significantly over the years, thanks primarily to the Michael Vick bust and the rescues – like Best Friends Animal Society – that fought to save his victims. Says Trish on the subject:

Believe it or not, I think we have Michael Vick to thank for raising the profile of fight bust dogs. The fact that his dogs were assessed as individuals was groundbreaking. Before this, most fight bust dogs were euthanized.

Jim Gorant’s book, ‘The Lost Dogs,’ is essential reading for anyone who loves Pit Bulls. The first part is hard to read, with some tough details about dog fighting, but later on it tells what happened to each dog and their journey to new, happier lives. The fact that so many of his dogs did so well, in sanctuaries and eventually in homes, paved the way for assessing dogs from other busts and adopting out those, like Theodore, who showed no aggression.

Vicktory Dogs such as Cherry, Ray, Handsome Dan, Hector the Pit Bull, and so many more, put beautiful, perfect faces to this horrendous issue. In the years after they were saved from Michael Vick, they helped spread the word about the horrors of dogfighting. They proved how wonderful they could be as family members, Canine Good Citizens, service dogs, therapy dogs, and so forth. Some, indeed, are still spreading the word.

But not all dogs get over their dog aggression, and really, that’s not the end of the world. Long before Theodore was adopted by Trish (or had even been born), she and Barry had a Pit Bull named Buddy, an ex-fighting dog who was disposed of in a dumpster in Chicago. Barry saved Buddy before he met Trish, and while Buddy was always wary of strange dogs, he came to be completely fine around those dogs he was familiar with.

Says Barry:

While living in Brooklyn, I found an apartment with a small backyard, and soon became friends with neighbors who had two dogs and no backyard. I was determined to find a way their dogs could also enjoy my backyard. I put a muzzle on Buddy, brought in one of their dogs, and watched closely. It wasn’t long before they were existing side by side with no problem at all. I was extremely cautious and gave it plenty of time until I was confident there was no problem with removing the muzzle.

I had long thought that Buddy’s aggression was because he assumed he’d better attack another dog before they attacked him. Getting Buddy happily living with other dogs after using the muzzle in this manner seemed to back up my theory. After he’d been around another dog long enough to convince him there was no threat he was fine. I’d simply put the muzzle on him and let them do as they may for several days. Eventually he even learned to play with other dogs who were determined to teach him.

With time and the right resources, I’m convinced almost every dog of this type – that is, a dog brought up in the dogfighting world – can go on to make a great companion. After all, only one remaining Vicktory dog was court ordered to stay at Best Friends Society, and even that one – Meryl – continues to make great strides to this day.

But as Trish Loehr points out, most dogs rescued from dogfighting don’t get the resources of the Vicktory dogs. “Unfortunately,” she says, “most fighting dogs don’t go home with the thousands of dollars Vick had to pay for the lifetime care of his dogs, so the resources aren’t usually there to help the ones with severe problems.”

It’s the same old problem – too many dogs and not enough people or money to do right by them.

How Can We Put An End To Dogfighting?

This is what it all comes down to. We can talk about how evil dogfighting is, but at the end of the day, is it enough to end the awful sport? And if not, what’s it going to take?

Says Trish Loehr:

I think the visibility and press the Vick dogs got has kept the issue in the public eye. Seeing groups like the ASPCA and HSUS (as well as many smaller organizations) seizing dogs and prosecuting dogfighters, people are learning the signs to watch for, and are reporting it more often. The penalties are increasing as well – compared to the mere two-year sentence Michael Vick got, Theodore’s old owner is now serving eight years in prison.

I do think the appeal of blood sports is waning – every generation seems more humane toward animals than the last, and I truly believe that one day the last fighting dog will be unchained and this cruel “sport” will die. I really hope it happens during my lifetime. In the meantime, regular folks need to keep an eye peeled for signs of dogfighting, and report it.

Trish also points out that the ASPCA has a great list of ways YOU can personally help stop dogfighting. I’ve paraphrased them below:

1. Support stronger laws against dogfighting, e.g., longer sentencing for dogfighters (eight years is still nowhere near enough) and felony charges for spectators (if there’s no money in the sport, there’s no sport).

2. Contact your local media and alert them to the cruelty and dangers of dogfighting.

3. Contact your local law enforcement and tell them how important it is that combating dogfighting become a priority.

4. Keep an eye out for signs of dogfighting in your area.

5. Protect your pets – dogfighters have no qualms with kidnapping your dog or cat to use as a bait animal, so never leave them outside without supervision.

6. Adopt a Pit Bull and have some pibbling adventures of your own.

7. If you already have a Pit Bull, love them and care for them like they deserve, and don’t be afraid to brag about how great they are. (By the way, my Pit Bull is totally awesome.)

8. Volunteer at your local shelter and help keep as-yet-unadopted Pit Bulls mentally and physically fit.

9. Educate others about the evils of dogfighting.

While I hope against hope that dogfighting will one day become a thing of the past, I’m not as confident as Trish that that’ll ever be the case. My faith in humanity is strong indeed, but it’s the kind of faith that I’m ashamed of. Which is to say, I have faith that some portion of humanity will always be vile – to dogs, to other humans, to the world around us.

Having said that, I have no doubt that we can, at the very least, turn dogfighting into a shameful and rare activity. As ever, it’s all about education and legislation. We need to make dogfighters and dogfighting spectators terrified of the consequences of their actions with appropriately harsh prison sentences. We need to spread the word about the signs of dogfighting and how to spot them. And we need to tell the world that the victims of dogfighting – Pit Bulls like Theodore or The Mighty Finn or Handsome Dan or Cherry – are wonderful dogs who deserve love, admiration, and belly rubs out the wazoo.

Dogfighting information provided by the ASPCA & HSUS

Pibbling with Theodore & Loehr Animal Behavior

Featured image via ASPCA